Hockney: A Reintroduction

by Diana Cenat

Before visiting David Hockney: Drawing from Life at the Morgan Library three weeks ago, I could wrangle this short list about the artist from the recesses of my mind:

- He made a series of swimming pool paintings.

- He loves the color blue.

There was also a vague recollection of Miranda July's lovely short film and essay inspired by Hockney’s Nicholas Canyon painting, but like many things I’d tried to consume in 2020, the particulars didn’t stick. It was more of an honorable mention than anything else.

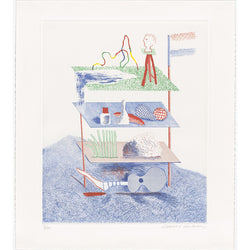

The colors sing! (And not just in blue.) Mundane, everyday scenes come alive in his work. Leaning into the frames, there was an overwhelming sense that something was shifting in me. In that moment, I realized how much my imagination had atrophied in the last year, reducing everything to black and white, and stifling my ability to dream.

As I toured the exhibit, a through line in Hockney’s work became clear. Here is an artist sure of his abilities because he’s been so anchored by the many loves in his life, whether it be landscape, lover, family or friend. With that security, Hockney has found the freedom to try a plethora of mediums to capture the same subjects again and again—giving you something new with each piece without losing his attachment to them, or his creative exuberance. Hockney wields time the same way he uses any other tool at his disposal, whether it be to catalogue twenty days or twenty years. Watching him revisit a familiar face with watercolors instead of pencils was thrilling. Studying that same face as it changed over the years was like following a relationship very closely; I didn’t know these people, but it felt like I did.

After months of feeling unmoored by what seems like a never-ending horror show, I left the exhibit invigorated and emboldened by this chance to see with renewed perspective. Instead of letting it run roughshod over me, I would try to use time the way Hockney does: as a utensil to create new, vibrant markers in my life that are tethered to who and what I love, instead of the innumerable things I cannot control.